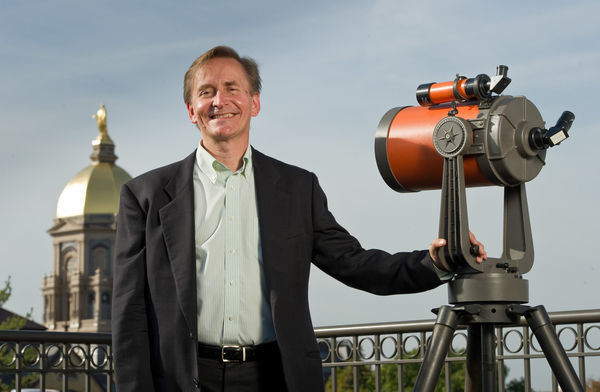

Prof. Peter Garnavich of the University of Notre Dame Physics Department was recently interviewed by WNDU about sun spots.

http://www.wndu.com/news/specialreports/headlines/Tracking-sun-spots-246430911.html

It has been a winter to remember! For many of us, this is reminiscent of the winters during the 1960s, 70s and early 80s. There have been long periods of cold, huge piles of snow and strong winds to pile it up. Of course, this is just one winter; it doesn't mean the climate is shifting. The biggest factor of our climate is the sun. No sun, no life as we know it. Too much sun means no life either.

“We do live on a wonderful planet with perfect temperatures at a special distance from the sun and hold in heat,” said astrophysicist Peter Garnavich. “We don't know what knobs change things on our planet. It may well be that the long-term changes on the sun have a huge effect on our climate.”

With current technology we've been able to measure the power output of the sun for only the past few decades. But there is one thing that astronomers have measured for hundreds of years.

“We look at the suns face and there will be little blemishes,” Garnavich said. “Galileo was the first to notice sunspots and called them blemishes.”

While it would seem that a blemish would cause the sun to be weaker, there is evidence the total amount of energy may actually increase. The sun goes through a typical 11 year cycle of sunspots, although each one is different. During the 1600's the early records show that there were very few sunspots…it was a quiet period called the Maunder Minimum. During that same period there was extreme cold in the one place on earth keeping records – Europe. Many call it the little ice age.

“There may be a correlation between long-term solar activity and earth climate it is certainly possible,” Garnavich said. “The Maunder Minimum seems to suggest there was a cool period in the 1600s that correlates with this lack of sunspots. That may have been a coincidence. It's hard to tell on a global basis back in the 1600s what was going on. There is a possibility the long term variation and magnetic cycle can affect climate.”

In this country, there is evidence of extreme cold, including the "year without a summer" in the early 1800's, another very cold period in the decades around 1900, and then the warm up over the last 100 years. The sunspot cycle seems to correspond with some of those fluctuations.

“This is the cycle we are in right now and we should be at maximum…and you can see how small the peak is,” said Garnavich. “It is one of the weakest maximums in history.”

There are an increasing number of solar scientists worldwide that are wondering if the sun is "falling asleep" again as the sunspot number diminishes. Could another Maunder Minimum be coming? If that's true, then we might see more and more winters as cold, or even much colder, than we just had. But, just like the weather, the sun is not something we can forecast perfectly.

“It's a phenomenon we don't understand,” Garnavich said. “We are going to need to collect more data and just see how these sunspot variations go.”

It's kind of like me saying before a snowstorm "if the track of this storm is a little different…blah, blah, blah". We just don't know what the future holds. Here's the thing though, a colder planet for 100 years would be tough for mankind to endure because we have to stay warm and we have to grow food. Being an optimist, I'm sure we'd find a way.